Page 19 from: January / February 2005

important steps taken towards the future establish-

ment of a global regime governing ship dismantling.’

Ross Bartley, BIR’s Environmental & Technical

Director, points out that the world recycling organi-

sation has been actively involved in discussions sur-

rounding the future of shipbreaking which, he con-

tends, have been moving steadily in the direction of

an ‘environmentally sound management’ regime. ‘We

support an improvement in standards to protect the

environment, human health and working standards,’

comments Mr Bartley. To get everyone around the

world to a good performance standard, he adds, ‘a

legal framework has got to be in place’ while those

spending money on meeting these standards need to

be confident that the investment will mature in the

form of ships coming forward for breaking.

Free and fair access

Underlining the importance of ‘good practical

implementation of even standards’, Mr Bartley

insists any global regime must enshrine ‘free and

fair access to ships for breaking’, such that any facil-

ity meeting the required standards is allowed to

pitch for business from any source. He also stresses

that the creation of any such regime will require

financial support.

Of course, this raises the thorny issue of who

should pay. A widely-held view is that shipowners

themselves, including governments in the case of mil-

itary vessels etc, should be responsible for these costs.

In the UK, a recently-released House of Commons

Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Committee

report – which drew on evidence from government

ministries, environmental groups and shipping

organisations among others – argues that ‘it would be

extremely difficult to assign responsibility for the way

in which a ship is dismantled to any but the current

owner’. And it adds: ‘We accept that it may be difficult

for smaller ship owning companies to assess the qual-

ity of dismantling facilities and we therefore recom-

mend that the government consider how an interna-

tional standard could be developed, which could be

used to certify qualifying dismantling yards.’

The report urges the government to work to

ensure the International Maritime Organisation

(IMO) ‘gives priority to producing an international-

ly binding agreement which sets out how ships

should be dismantled’. And it emphasises: ‘Such an

approach must avoid the difficulties associated with

the current tortuous arguments which try to deter-

mine when a ship becomes waste.’

Late last year in Geneva, the Basel Convention

confirmed that ships can be considered toxic waste

under international law and that its 163 signato-

ries must control the export of ships under the

terms of the Convention. Thus, they must prohibit

exports without the consent of recipient countries,

and must ensure that shipbreaking is performed in

an environmentally sound manner while minimis-

ing the transboundary movement of hazardous

wastes. The latter obligation can be expected to

increase demands for decontamination of ships pri-

or to export which has been urged by the shipbreak-

ing countries of India, Bangladesh and Turkey.

It is argued that such developments will create

new demand for the development of ‘green’ ship

recycling capacity in developed countries.

Little incentive to develop facilities

The House of Commons Environment, Food and

Rural Affairs Committee study was sparked by the

controversy surrounding Able UK’s bid to dismantle

ships from the US auxiliary fleet, which have

become known universally as the ‘ghost ships’ (see

separate box). The committee acknowledges that a

lack of suitable dismantling facilities in developed

countries represents ‘a significant barrier to respon-

sible ship dismantling’. And it

continues: ‘Given the economic

advantages of dismantling

facilities in Asia, and the diffi-

culties faced by companies such

as Able UK, there is little

incentive for companies here to

develop ship dismantling facili-

ties.’

Meanwhile, the Co-ordinator

of Greenpeace’s international

shipbreaking campaign

Marietta Harjono believes ship

owners and shipping organisa-

tions have been guilty of taking

insufficient action in the past

and should be prepared to take

on greater responsibilities with

regard to dismantling. Noting

that the environmental lobby

group has long been seeking ‘a

S H I P B R E A K I N G

19

Indian federation calls for

zero duty

India is one of a number of countries to have been

severely affected by the recent dramatic decline in

shipbreaking activity. In a bid to stimulate imports of

ships for dismantling, the Indian government

reduced the import duty on these vessels from 15%

to 5%, but this appears to have had little impact

on activity levels. The Indian Scrap Recycling

Federation is now calling on its government to reduce

the duty from 5% to zero in its forthcoming budget.

India was responsible for scrapping some 3.3 mil-

lion tonnes ldt in 1999, but this total fell to around

1 million ldt last year. Shipbreaking statistics for the

last four year are as follows:

Year No of ships Scrapped Tonnage (ldt)*

2001 416 2 938 810

2002 390 2 680 483

2003 375 2 138 614

2004 226 1 000 000

* India was recently paying around US$ 400-405 per ldt – around

twice as much as the prevailing ferrous scrap price. However, it

should be borne in mind that around 70% of the scrap from these

ships is going for re-rolling.

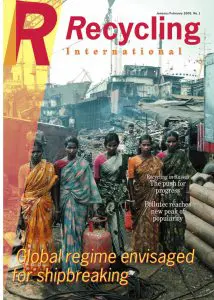

Shipbreaking in Asia is still carried out by

manpower.

Marietta Harjono, Co-ordinator of Greenpeace’s

international shipbreaking campaign:

‘Companies that seek to raise their schip

scrapping standards are losing business to

those with lower standards.’

Ross Bartley, BIR’s Environmental & Technical

Director: ‘The future of shipbreaking is moving

steadily in the direction of an environmentally

sound management regime.’